September 18, 2015

America-born lawyer Matthew Karanian went to Western Armenia in 1995 as a hitchhiking young man, and long before Turkey had relaxed its rules regarding Armenians tourists visiting their historic homeland in Western Armenia, Cilicia and other regions where their parents or grandparents were born.

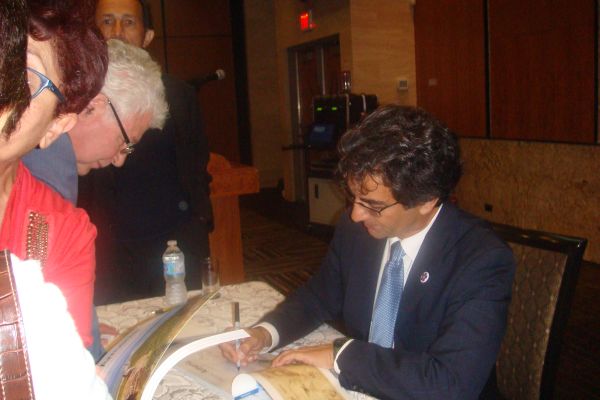

Karanian has revisited historic Armenia many times since and every time he has photographed buildings which have barely survived Turkish ethnic and religious hatred, treasure hunters and army cannons which have used Armenian churches for target practice. “Historic Armenia: After 100 Years” is the result of Karanian’s peregrinations. The 176-page book, with 125 color photos and maps, is a welcome addition to the growing library of recent books about historic Armenia, outside of the Republic of Armenia.

During his book tour in Toronto, which was sponsored by the Armenian General Benevolent Union, Hamazkayin Cultural Association , Armenian Association of Toronto and Bolsahay Cultural Association ( Sept. 13), Karanian described his book as a “populist, non-scholarly” look at what’s left of our collective cultural sites now occupied by Turkey. Telling aspect of the book are photographs of the way our churches and monasteries looked before 1915 and how they look now. In some instances, as in Van, there’s nothing left except poke-marked fields, testimony that after destroying the structures, Turkish treasure hunters had dug into the building foundations hoping to find jewelry Armenians had hidden before the Turks marched in to kill or to deport them.

“Everything has been wiped out in Van. The only buildings which stand are two mosques. The scene is repeated elsewhere. The blind treasure hunters ignored the real treasure of Armenian art in search of gold,” said Karanian.

On the reverse side of the coin, he remembered that when he went to Aghtamar nearly 20 years ago, the Sourp Khach (built in 915) was desolate, in bad shape and without an altar. Since then the cathedral has been restored and Holy Mass and even baptisms have been held there. Karanian also mentioned that while everyone knows about Aghtamar, there are three more islands in Lake Van which have churches. Because they are relatively inaccessible, few people visit them. Ironically, this has meant some of the churches are in reasonably good shape. One such island is Gdouts.

Another irony, Karanian said, is that while the churches were in military-controlled areas, they had remained reasonably intact (unless they were used for target shooting). But once the military had departed, treasure hunters invaded the sites.

Karanian then took the audience to Ani. The capital of the Pakradounis had a population of 100,000 and so many churches that the legend of 1,001 churches was born. He also reminded the audience that the main Ani cathedral is believed, by many scholars, to be the precursor of Gothic architecture which flourished in Europe a few centuries later. Karanian described the gorge which separates the area from the Republic of Armenia as “our unhealed wound; our scar.”

Karanian then directed the audience’s attention to the relatively unknown Meren Cathedral, just west of the Republic of Armenia. Here again, treasure hunters have dug six to eight feet into the building foundations in search of gold. As a result, the ancient church is in imminent risk of collapse. Another church, which was almost intact until 1955, was blown into smithereens as a result of deliberate army explosion, he said.. Karanian added that the explosion had such force that shards of the church can be found scattered on the hills surrounding the buildings.

The author said that one of the main reasons he wrote the book was to provide a testimony of what exists now. “I wanted to build a benchmark as to what is there in 2015,” he said. This, of course, is a message to the “current custodians”.

While looking for ancient buildings, Karanian also went “hunting” for hidden Armenians, Islamized Armenians, people who recalled that they had Armenian grandmothers or grandfathers. He told about meeting 82-year-old Baidzar who married at Sourp Giragos Cathedral in Diyarbakir at that age because her previous wedding had not been a Christian one. Another hidden Armenian Karanian met is Asia, born I 1920. Her 10-year-old mother had been saved by a Turkish soldier because he was struck by his beauty and wanted to marry her. Some 10,000 fellow Chonkoush Armenians weren’t so lucky. They were pushed into a deep gorge to die. Asia’s mother had spent her whole life hiding her identity, but she had told Asia that they were Armenian. In the town of Zara, Karanian met the last Armenian left there. He is married to a Muslim and has two children.

Searching Sebastia and Erzurum for relics of our homeland is a vain venture because there’ nothing left. There are few traces of Armenian presence in Kharpert. Karanian said that in 1910 about 80% of American-Armenians were from Kharpert. What drove so many to leave long before the Genocide?

Writer and musician Raffi Bedrosyan, who has been active in the restoration of Sourp Giragos Cathedral, and in the past two summers had led large groups of hidden Armenian to Armenia, introduced Karanian and gave an overview of recent development in Western Armenia where Kurds are battling Turkish oppression.

By Jirair Tutunjian